What is a registered design?

View more

Apps are part of the daily lives of anyone with a smartphone, which is most people. Apps are designed to fulfil a range of uses, such as to entertain us, to inform us and/or to help us be more organised. Some apps allow us to control external devices such as smart bulbs and connected speakers.

Before considering the Intellectual Property rights available for apps, it is first vital to consider the features of the app that might be valuable to protect.

When people think about protecting innovation, they usually think about patents. Patents are there to protect the way an innovation works. In the context of an app, this might be a new way of connecting to an external device which is particularly fast or secure, or a new way of encoding an audio stream for transmission across the internet, which is particularly secure or particularly suited to poor internet connectivity. Patents are often unavailable (at least not in the UK and Europe) for protecting the concept of a new restaurant ordering system, a new booking system, or a new game. This is because there are certain exclusions from patentability (such as business methods, methods of playing a game, mental acts, presentations of information, methods of treatment or diagnosis). If the innovation lies in one of these excluded areas, then patent protection is likely to be unavailable for the broad concept of the app (though it may be that some particular feature of the data processing used by the app is patentable). From experience, we find this is often true of apps, where the prospects for successfully obtaining protection for the broad concept of an app is difficult. Whilst it may be possible to obtain protection for a particular data processing method used in an app, you may decide that it would be too easy for third parties to compete with you by producing an app that looked similar, but just used an alternative data processing method to achieve the same or a similar effect.

Another form of protection that app developers should consider is design rights. In the UK and the European Union, these are known as registered designs and unregistered designs. In the US, registered designs are referred to as design patents. Unregistered designs are rights that arise automatically, but have a shorter duration than registered designs (usually 10 years in UK and 3 years in the European Union, compared with 25 years for UK and EU registered designs), and also require a right owner to demonstrate that their design was copied, making them more difficult to enforce in many situations. For this article, we focus on registered designs.

A registered design provides protection for the visual features of an article. The article may be a physical product, surface decoration, or one or more elements of a graphical user interface. Any third party design or product that provides the same overall impression as the registered design is considered to be an infringement, and the rights holder has the power to stop the sale and use of that third party design or product, in the same country as the registered design. Registered designs must also be sufficiently different from existing designs that would have been available to designers.

One of the most powerful aspects of registered design protection is that you can decide to “disclaim” one or more features of the layout from the scope of protection, meaning that such features are not taken into account when assessing infringement (or validity) of the registered design. By using disclaimers in this way, the registered design can denote that elements such as the aspect ratio of the screen, and the exact content in particular areas of the app, are not to be considered essential elements of the design. Other elements, such as particular icons, can be shown claimed, and therefore are to be considered essential elements of the design. It is not just a whole feature that can be claimed or disclaimed, but part of the feature (such as the rounded corners of a box), and the specific colour of the feature.

Let us consider a menu screen of an app. There may be some artwork in the background, and a collection of buttons. The buttons will be provided in a particular location on the screen, and each button will have a particular shape, size and label. A simplified example is shown below:

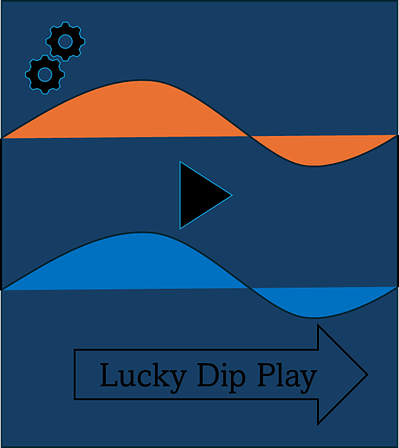

Here is the original main screen:

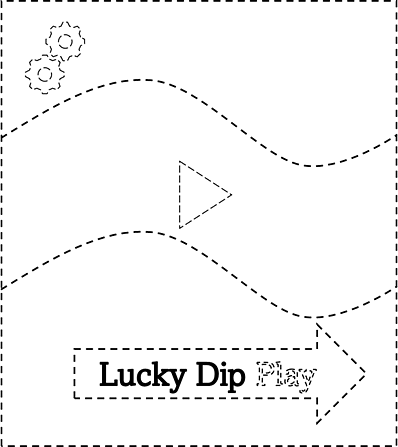

This is for a game where it is possible to modify settings (by clicking on the settings gear icon) to play the game with different difficulties and other preferences. The user plays the game by clicking on the play icon in the middle of the screen. The user can also select a “Lucky Dip Play” where settings such as difficulty and character are randomised and a game starts straight away.

Here, a suitable filing strategy might include one or more of the following variants:

1. The screen as it appears.

2. The screen as a line drawing. No claim is made to particular colours.

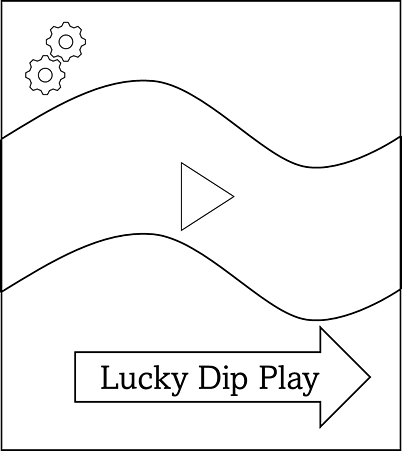

3. The screen as a line drawing, with the background disclaimed.

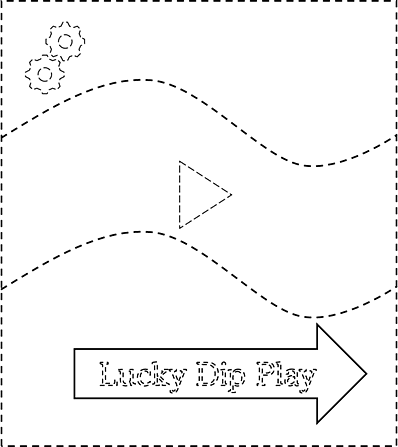

4. The screen as a line drawing with everything but the “Lucky Dip Play” button disclaimed, including the writing.

5. An alternative version where some of the text of the “Lucky Dip Play” button is claimed, but the button itself is disclaimed.

It is worth noting that the validity of designs 4 and 5 at least may be questionable because so few features are included in the design, but they might still be valuable where it would be difficult for a third party to be certain that either design would not be considered valid.

By filing registered design applications with the variants 1 to 5, not only is there strong protection that could be asserted in the UK against someone producing a direct copy, but there are also broader scopes that could be asserted against someone producing versions that look slightly different but still include some of the important features.

This article is intended to provide a basic introduction only, and it is strongly recommended that app designers seek specific advice from a designs expert who can advise them on how best to protect their specific app.

To seek our detailed advice on registering designs to protect your app, please contact your usual Hindles attorney, or Chris Cottingham.

View more

View more

View more

View more

View more

View more

View more

An occasional newsletter about patents, trade marks, designs and other intellectual property matters.